How Big IS Big?

The completion of GPO Building 3 (at right) in 1940 brought the total floor space of the GPO facility in Washington, DC to 33 acres.

The United States Government Printing Office (now known as the Government Publishing Office) was called the “Largest Print Shop in the World” for many decades beginning around the turn of the twentieth century. Everything about the operation at that time and through the 1970s seems, especially in our age of miniaturization, just huge. The plant, affectionately called “The Big Red Buildings,” eventually expanded to four structures on North Capitol Street amounting to 33 acres of floor space. The annual production of documents was nothing short of vast, reaching well into the billions of copies annually by 1940, when 5600 people worked there. At its peak, in the 1970s, our employee roll reached over 8000.

It’s very easy to talk about “the biggest,” especially when that description is part of the folklore of a place. Putting some concrete definition around that is a little harder. Photos of the GPO plant with machinery stretching off into the distance help, but only a little.

In our historical collection I recently came across published catalogs of GPO’s machinery and equipment from the 1920s, 1940s, and 1980s. These catalogs were used by plant planners and schedulers in organizing and distributing work. The catalogs are censuses of our machinery, and they give additional form to our notion of how physically big the “big shop” actually was.

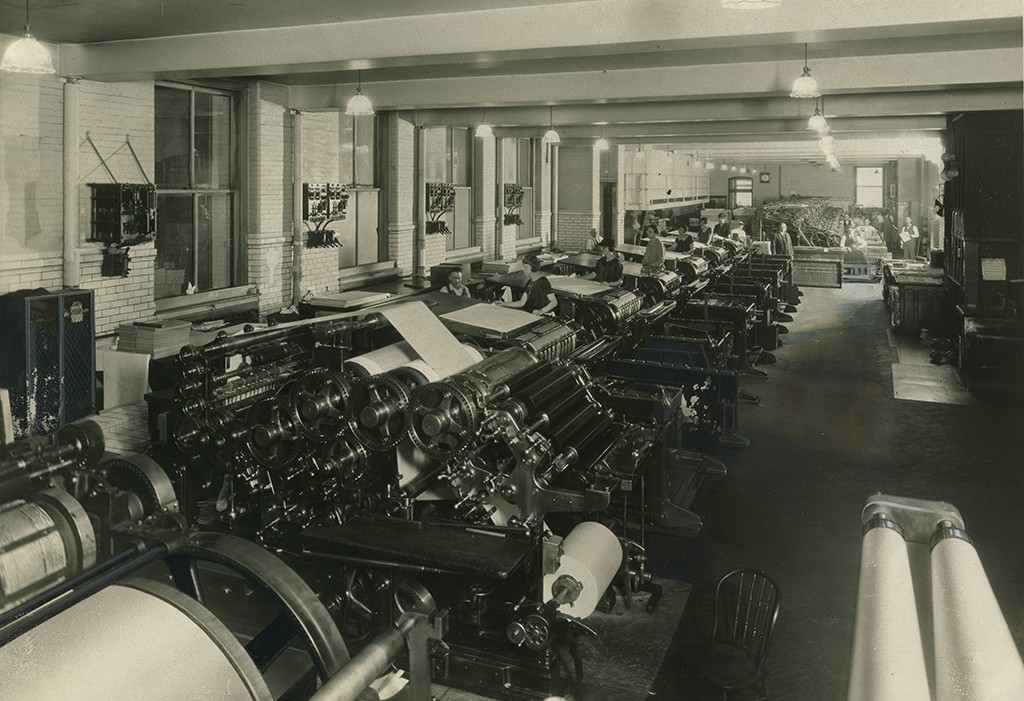

The catalog for 1926 lists 29 rotary web presses, some of which had a footprint as big as a Washington, DC studio apartment, 103 flatbed presses, the workhorses of the shop, 15 platen presses, 19 rotary presses, 4 web platens, 5 tabulating card presses, and 7 miscellaneous presses, a total of 182 presses, not including 31 proof presses.

Web-fed rotary presses in the foreground, sheet-fed flatbed cylinder presses stretching into the distance, 1920s.

In 1942, the total is again 182: 22 rotary web presses (3 of which printed the Congressional Record and the Federal Register), 70 cylinder presses, 31 cylinder flat beds, 4 rotary presses, 14 platen presses, 8 Miehle Verticals, 7 envelope presses, 16 tabulating card presses, and (very much to my surprise for this time period) 10 offset presses. At this period, GPO was still an almost militantly letterpress shop, and would be until well after World War II.

And we mustn’t forget the 45 or 50 proof presses, which seem to have been scattered around the various divisions a bit like photocopy machines in a later era.

Compare this with the printing shop that Congress acquired from Cornelius Wendell in 1861, which was then thought of as the largest shop in Washington and one of the largest in the nation. Its pressroom was described in the annual report of the Superintendent of Public Printing in 1860: 23 Adams presses (almost certainly Adams bed & platen presses), 3 cylinder presses, and the steam engines to run them. There may have been a few iron hand presses used for pulling proofs, but they aren’t mentioned (curiously, since the published inventory is detailed down to 19 spittoons in the composing room and the velvet armchairs in the Superintendent’s office). Very large, for 1861, but just a prelude.

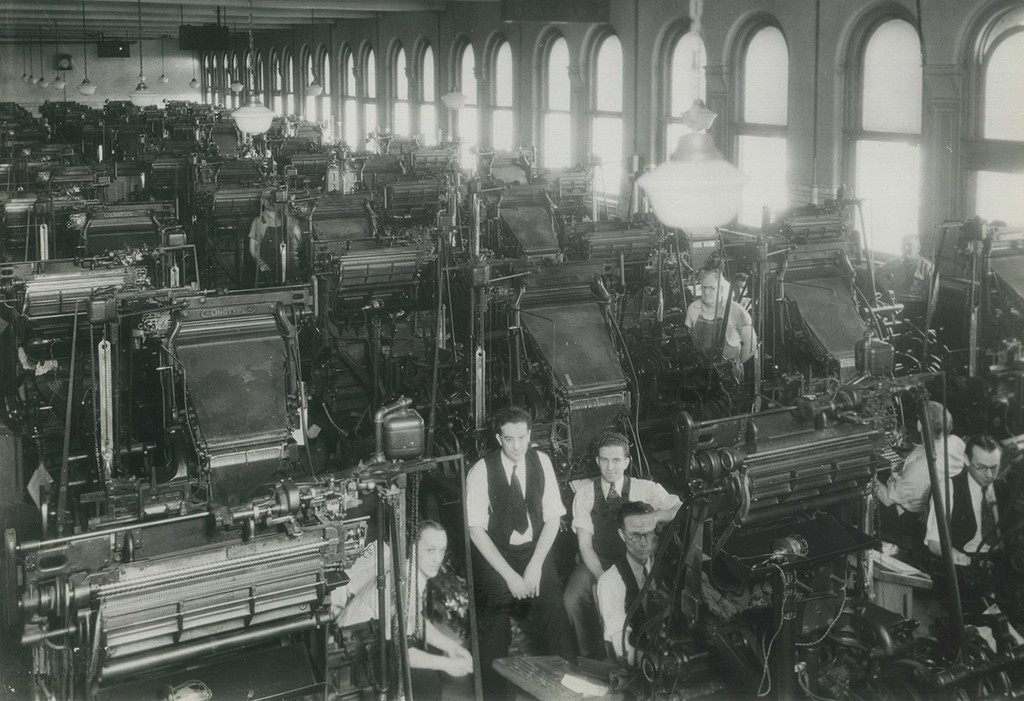

Back to 1942, in the Composing Division there were 100 Monotype “D” keyboards, 114 Monotype casters (14 only casting sorts), 8 Monotype display casters, 9 Monotypes for casting furniture. Of 129 linecasting machines, 95 were Linotype, 34 were Intertype. Beyond the substantial floor space this required, consider the weight involved here: a model 5 Linotype with a single magazine is supposed to have weighed 2450 lbs. (about the same as a classic VW Beetle) before any lead was added to the pot for casting into type.

The Linotype section, about 1920. From an initial order of 40-some in 1904, GPO rapidly added machines – 129 by 1942, each weighing over 2400 lbs.

The Monotype keyboard section, 1916. After the introduction of machine typesetting in 1904, Monotype also grew rapidly, well over 100 keyboards and casters by the 1920s, the largest installation of Monotypes in the world. Consider the sound of over 100 Monotype keyboards operating at the same time.

And then there was the Bindery, where there were book presses, cutting, gathering, folding, stitching, backing, rounding, casemaking, bundling, sewing, oversewing, trimming, and wrapping machines. And still at this stage 15 ruling machines, which put the pale blue and red lines on the pages of ruled ledgers that remained a big line of business for GPO, not to mention gumming machines that made pads of paper.

The binding operation was almost unbelievably diverse and comprehensive. There was equipment and expertise for every kind of binding from the simplest of folded pamphlet to the most elaborate leather binding, from wire-bound calendars to high-quality library bindings.

A battery of ruling machines, about 1920. Ruled ledgers and record books, as well as ruled pads, were a huge line of business for GPO well into the 20th century.

The Tests and Technical Controls Division had, among many amazing toys, 6 machines for casting ink rollers, the photos of which have a very Buck Rogers feel. Not to forget the four 7 1/2 ton furnaces for casting type metal (and the smaller 5 ton and 200 lb. furnaces). Those 7 1/2 ton furnaces were something like 6 or 7 feet across. About 15 tons of type metal was remelted and corrected for use in the typesetting machines every day. By the 1940s, GPO was processing almost 10 million pounds of type metal annually.

Now we fast forward to the last time these equipment and machinery inventories were published, 1980 and 1988. GPO’s peak production years of the 1960s and 70s were over, employment was declining from the peak of almost 9000 in the 1970s, and roughly 75% of GPO’s work was being procured from private sector businesses. Economic and political pressure saw the agency growing smaller for the first time in a century.

In the 1980 and 1988 inventory, the dizzying variety of presses seen 50 years before is replaced with a stark line dividing the office: offset vs. letterpress. The Congressional Record and Federal Register were still produced on the four group 59 web letterpresses. It was in this period that the Record saw its last hot metal edition. In all there were 37 presses in the Letterpress Division in 1980, 17 in 1988. There were 46 presses in Offset in 1980, 38 in 1988. The catalogs no longer show all machinery, so although there were still a few proof presses around, they aren’t listed.

Also not listed are any of the Linotype machines, Monotype keyboards, or Monotype casters. As the hot metal operation drew down through the 80s, the machines were decommissioned and mostly sold for scrap. Two Intertype machines, two Ludlow Typographs, and a couple of Vandercook proof presses retired to a shop in the Bindery, where they remain, the last remnants of the largest hot metal operation on earth.

It does need to be said that the production in the plant in the 1980s was still prodigious, and although the number of presses was reduced the newer presses were more productive than their predecessors.

And the pressroom of 2015 is yet another vastly changed landscape. No letterpresses remain. Offset plates are produced directly from digital postscript files. The GPO of 1942 produced almost entirely black ink on white or colored paper, no color work. Many of today’s presses are full color. In all there are 23 presses in the 2015 pressroom: 9 sheet-fed, 4 envelope presses, a silkscreen press, and 9 web presses. Among those 9 are two of the longest serving presses currently, the group 86 web offsets installed in the 1980s. That also includes the latest and most impressive addition in many years, a Timson “zero make-ready” press, which requires no stop for form or roll changes and delivers very high productivity and efficiency.

GPO’s growth peaked by the 1980s, and by the 1990s the impact of the digital revolution was felt in ways as dramatic as the machine typesetting revolution of the turn of the twentieth century, which had sparked the tremendous growth in demand and capacity. The shift from printed documents to online publications, in which GPO’s work with computer typesetting had played an early role, now saw the demise of publications that had been GPO mainstays for nearly a century. In 2015, in a changed but still quite large shop, GPO continues to produce a wide variety of printing and binding work alongside the cataloging, organizing, and disseminating of digital publications that continue GPO’s mission of keeping America informed.