Depictions of Printing in Deaf Periodicals

An interesting intersection of Deaf history and print history in America took place early in the nineteenth century. As is well documented by scholars Jack Gannon, John Vickrey Van Cleve, Susan Burch, and R.R. Edwards, among others, the story of the “silent,” or “deaf press,” had its modest beginnings in 1836, starting with the Canajoharie Radii (site of the Central New York Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb), a paper printed by a Levi S. Backus, for the benefit of both deaf and hearing readers. The success of this publication led faculty at the American Asylum for the Deaf (Hartford, Connecticut) to start a paper at that school, which later became The American Annals of the Deaf in 1847. The Deaf Mute, out of the North Carolina School for the Deaf, set up shop soon after, in 1849 (Gannon 238-250, Edwards 111-13).

After mid-century, the success of The Annals and The Deaf Mute snowballed; there were more and more papers made by and for the deaf. There were independent newspapers, such as The National Exponent out of Chicago and the National Deaf Mute Gazette out of Boston, but perhaps more significant were the weekly and monthly papers produced by deaf institutes from Louisiana to Kansas (and in Canada as well). At its height, this network, dubbed “The Little Paper Family” by deaf editors in the 1890s, boasted at least fifty significant publications (Gannon 247, Van Cleve PTO 98).

For the most part, early Little Papers were sparingly illustrated, resembling the majority of U.S. periodical covers, in that they mainly mimicked the frontispieces of books. Similarly, early issues of LPF papers had minimal embellishments, but interestingly, as Beth Haller notes, these embellishments were always visually significant and almost always alluded to both “the visual nature of the deaf language and culture” and to the art of printing, suggestive of the evolving convergence of the two.

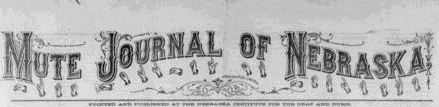

The Arkansas Optic, for example, featured a drawing of a large eye (5). The Canajoharie Radii and Mute Journal of Nebraska had banners in both English and the manual alphabet (figs 1, 2).

Fig. 1. Fingerspelled banner with seated figure reading (center). The Canajoharie Radii March 21, 1844. Canajoharie Library and Art Gallery.

Fig. 2. English and fingerspelled letters on banner of Mute Journal of Nebraska Vol. 5, No. 7, September 1878.

The nameplates (and later covers) of the New Jersey School’s paper, The Silent Worker, as well as journals like the Oregon Outlook, depicted detailed scenes of students at work setting type and rolling the press, or contained other references to text, like books or scrolls (figs 3-6).

Fig. 5. Student setting type using a Linotype machine. “Poster” cover from The Silent Worker, October 1920. Fig. 6. Various stages of the printing process (bottom margin). Cover from The Silent Worker, May 1922.

Deaf people have always been on the forefront of new communication technologies, and the nineteenth century was no different; by the late 1800s, just about every deaf school in the country had made the switch from hand presses to professional-grade Linotype machines and cylinder presses. They also had well-trained printing departments that could handle all aspects of the process, as is evident from this description of the New Jersey School for the Deaf’s print shop in the early 1900s:

… a much larger camera was purchased and in addition thereto a buzz-saw for cutting copper and trimming blocks, a beveler and the necessary chemicals for wet-plate making, the same as is used in all commercial shops. These improvements greatly facilitated the work of this department and also provided a means whereby boys could command high wages when they left school …. Next all three more linotypes will be added, making a battery of 6 machines, besides a Miller-Saw trimmer and a power stapling machine (Porter)

According to LPF scholars, the main goal of the papers, from their inception, was to “support the further expansion of academic and vocational instruction for deaf children,” and to “influence the character and values.” To that end, the papers often “gave advice on how to succeed in a hearing world” (Edwards 112-13). They emphasized independence as well as good behavior. But the papers (and the schools that housed them, for that matter) had also been created with the purpose of creating employable workers—deaf people who could become “proficient workers and independent citizens” (Buchanan in Van Cleve Deaf History 175). Schools (perhaps more accurately school boards) felt that since the state provided vocational and academic training, students were obligated to use this training to become “exemplary employees who would serve as informal representatives of all deaf persons” (176).

A specific example of this may be seen in the story of The Silent Worker. When in 1888 The Deaf-Mute Times changed its name to “The Silent Worker,” the editors explained in the September issue that “[the title] … indicates quite aptly what we wish each of our pupils to become.” Even the paper’s motto was a saying from Dionysius: “The foundation of every State is the education of its youth” (also inscribed on the Library of Congress). Editor George Porter himself later expressed the wish to develop in children “a full sense of the dignity of labor” (Buchanan 176). Porter and other editors like him, in order to achieve this goal, managed to make their print shops vital parts of the deaf schools, because, as Porter points out, they “provided a means” for making a living (an excellent means, it turns out—by 1880, deaf printers could earn up to thirty dollars a week) (Edwards 120). The papers and the shops provided an invaluable vocational training ground for students learning a trade that would employ deaf workers well into the twentieth century—a trade that, indeed, became what was considered by many a “traditional” deaf occupation (Christiansen 260-1).

It is clear even from this very brief history of the production of The Little Papers, that, for almost one hundred years, a very large proportion of deaf labor was vitally connected to the physical creation and production of texts. Deaf hands were intimately familiar with the handling of paper, the composition of type, with the creation of and making of photoengravings, with the inking of forms, with the continuous, rolling production and reproduction of images and words. Because of the hands of deaf writers, illustrators, and printers, Deaf images and words were shared on a national scale. The labor, the production of the hand, the hand of “silent workers,” resulted in reams of text—millions of words and images, in English, a language not entirely their own—a language with which, ironically, they had an ongoing, fraught relationship.

Works Cited

Burch, Susan. Signs of Resistance: American Deaf Cultural History 1900-World War II. New York: New York UP, 2002.

Christiansen, John, “Deaf People and the World of Work” in Deaf Way II, Carol Erting, et al., eds. Washington, DC: Gallaudet UP, 1994.

Edwards, R.R. Words Made Flesh: Nineteenth-Century Deaf Education and the Growth of Deaf Culture. New York: NYU P, 2014.

Gannon, Jack. Deaf Heritage. Maryland: National Association of the Deaf, 1981.

Grow, Gerald. “Magazine Covers and Cover Lines: An Illustrated History” Journal of Magazine & New Media Research. Vol. 5, No. 1, Fall 2002

Haller, Beth. “The Little Papers: newspapers at the nineteenth-century schools for deaf persons.” Journalism History 19.2 (1993): 43-50.

Harrington, Tom. “Brief History of the Little Paper Family.” LibGuides. Update 2010.

Hutchinson, Peter. “A Publisher’s History of American Magazines—Magazine Growth in the Nineteenth Century.” (pdf) Accessed 6 March 2016.

Porter, George S. The Silent Worker. October 1928 WRLC Digital and Special Collections.

Van Cleve, John V. and Barry A. Crouch. A Place of Their Own: Creating the Deaf Community in America. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet UP, 1989.

—. Deaf History Unveiled: Interpretations from the New Scholarship. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet UP, 1999.

—.“Little Paper Family,” in Gallaudet Encyclopedia of Deaf People and Deafness. New York: McGraw Hill, 1987.