Restoring A Coisne Stanhope Hand Press

While there are some gaps in our knowledge of the evolution of the hand press, one of the great leaps forward occurred about 1800–1810, when Charles Mahon, third Earl Stanhope, developed his ideas for a printing press, which was produced by the London engineer Robert Walker. And although there is some suspicion about the source of the ideas for the mechanism, Stanhope is credited with “inventing” the first all-iron hand press, and its success ensured its spread throughout Europe.

The French were among the first to latch onto the design, and these Stanhopes strongly resemble those produced by Walker in the same period. But the French presses are different in two respects: the T-shaped wooden base became a cruciform, and the leather girts used to propel the bed in and out, beneath the platen, became twisted rope.

Jennifer Protheroe Jones, Principal Curator – Industry, National Waterfront Museum of Wales, and I have been compiling and sharing as much information and as many photos of Stanhope hand presses as we can find. Jennifer focuses on the evolution of Walker Stanhopes, while my interest is in how the Stanhope evolved both in England and in other countries where they were produced (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden), as well as identifying how many that are extant and available for study. As of now, we have found information on 84 Stanhopes, 30 of which are in the UK; the rest are scattered throughout the world, with clusters in France, the US, Sweden, Australia, and individual presses in many other countries.

A comparison of photos of French presses with those from England, Scotland, and on the continent, reveals that both the cruciform base and the use of rope for the rounce are virtually unique to and used exclusively on the French presses. Lorilleux, Gaveaux, S. Berthier & Durey, Dulche, Gauthier, Bresson, Misselbach, Thonnelier, Giroudot, Frapié, Durand, Colliot, Rousselet, Tissier, and Coisne are some of the French makers of Stanhopes, Columbians, and Albions in the nineteenth century some of whose presses are recorded in our censuses. Unfortunately, I have found little biographical or other information about these companies and the individuals whose names they bear. Coisne’s presses are generally marked “Coisne Mécanicien a Paris” and little else.1 , 2

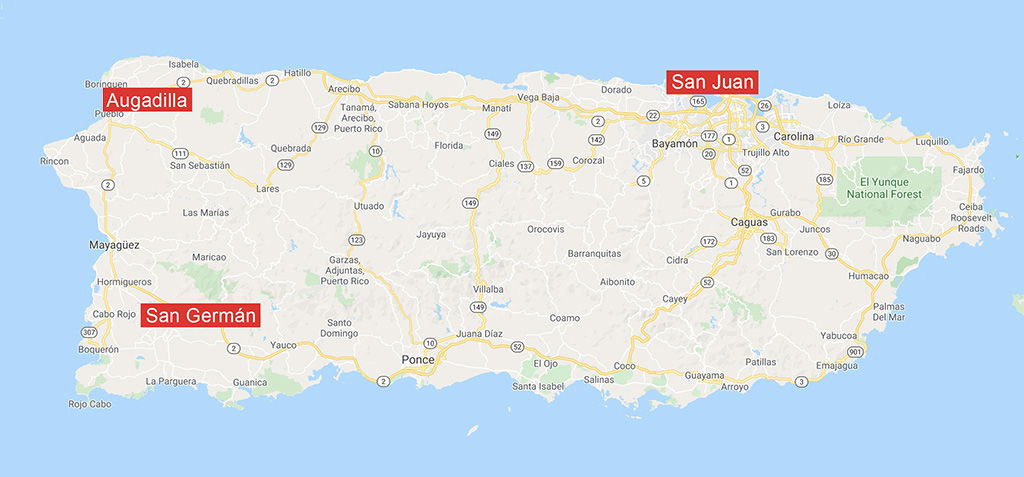

Recently, I was contacted by Paul Moxon, who had been asked by Museo Biblioteca La Casa del Libro (LCDL) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to help rehabilitate their three printing presses. These machines were a Coisne Stanhope hand press, an 8 × 12 old style Chandler & Price platen jobber (C&P), and a Vandercook No. 4 flatbed cylinder proof press. Paul, an expert on Vandercooks, asked me whether I would be interested in working on the Stanhope because he has had minimal experience with iron hand presses and none with Stanhopes. The C&P and the Vandercook would require pretty much all of the four days that had been allocated, so I agreed. And because a grant awarded to LCDL paid only for one person, and because I wanted to learn more about this Coisne Stanhope, I volunteered to go to San Juan at my own expense to do what I could to rehabilitate it.

We found that the three presses were essentially intact but dirty, rusty, and in need, in the case of the C&P and Vandercook, of both cleaning and tuning up, and replacement rollers, and some other parts. The Stanhope had considerable rust, and the bed was rusted in place, and some parts were missing and had been for some time, but replacements must be made; there are no “spare parts.” We set to work, assisted by staff, volunteers, and friends of La Casa del Libro. I will focus my report on the Coisne Stanhope, with a brief mention of the Chandler & Price—Paul can tell more about that and the Vandercook.

The Stanhope press in question has an interesting biography:

… we have an old French-made Coisné Mécanicien press, similar to the English Stanhope. This beautiful press was acquired in Aguadilla, saving itself from an ungrateful death, since it was going to be sold like old iron. It appears in Puerto Rico during 1858 in San Germán, the time of the revolutionary poet Lola Rodriguez de Tió. Transported by schooner to Aguadilla, she became part of the workshop of Don Rodulfo Hernández, editor of two weekly newspapers, in which José de Diego published articles and poems.

The foregoing is a transcription of a hand-written document at LCDL by artist Lorenzo Homar, one of the most important figures of the 1950s generation of Puerto Rican artists, recognized as a towering figure in the Puerto Rican graphic arts tradition.

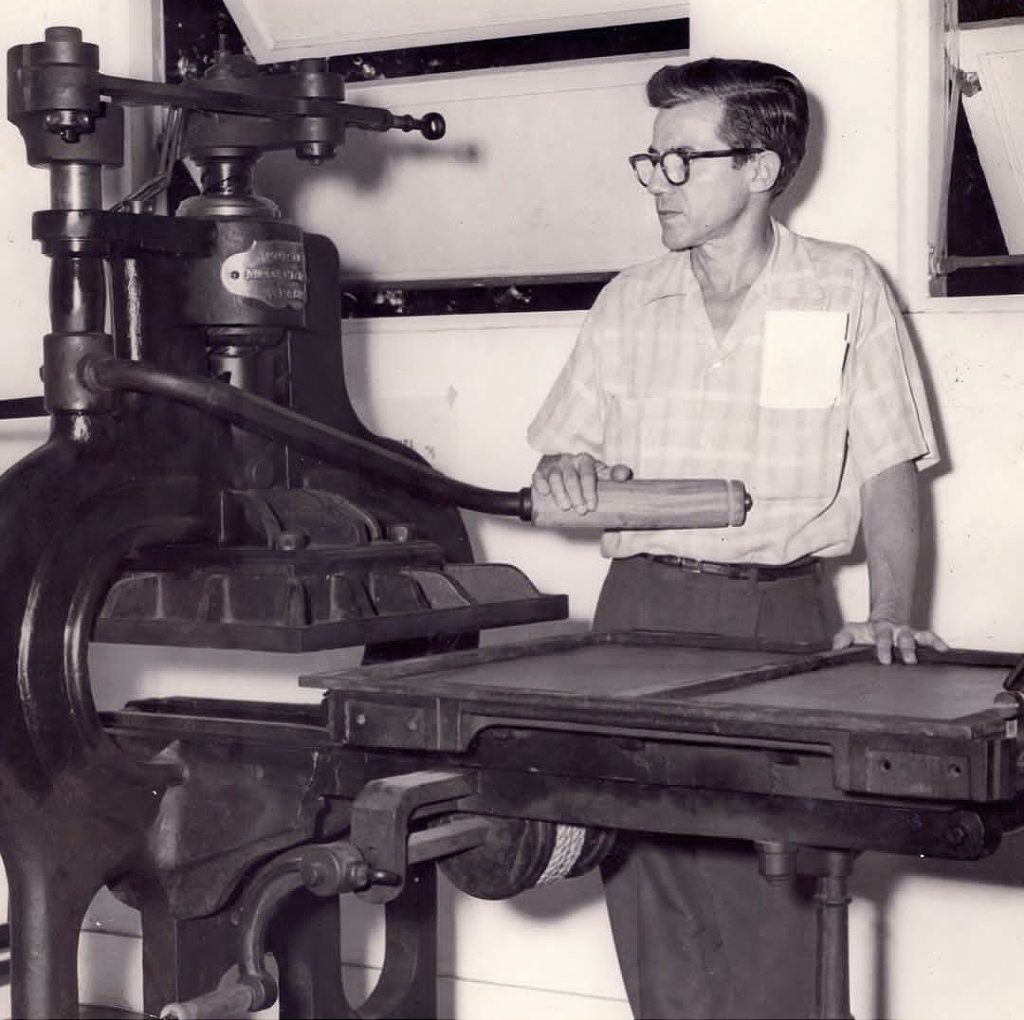

Lorenzo Homar at the Coisne Stanhope, circa 1967–70. Note the Coisne badge on the Stanhope. Now missing. (Courtesy of Museo Biblioteca La Casa del Libro)

Karen Cana-Cruz, Executive Director of La Casa del Libro, fills in the rest in the story:

In the late 1960s, Homar went to rescue the press at the suggestion of Ricardo Alegría, director at the time of Puerto Rican Institute of Culture (ICP), who received the press as a donation. The press was used in the Institute’s Graphic Arts Workshop by Homar, Antonio Martorell, José Alicea, and many other renowned Puerto Rican graphic artists. From there, the press went to the ICP’s School of Art, where artist Ida Nieves Collazo (Ponce, PR, 1941–1984) and Reinaldo Ríos printed the beautiful artwork Portafolio Ancla inspired by the press history. Soon after, the press fell into disuse.

In the early 1990s, María T. Arrarás, director of La Casa del Libro at the time, arranged for the school to give the press to LCDL to restore it and make it part of the exhibition on book arts, in accordance with the vision of Elmer Adler, founder of La Casa del Libro. Arrarás’s engineer husband, Edgardo Colón Stefani, rehabilitated the press and put it into use. In 2006, the LCDL building needed repairs and the presses remained on site while repairs were done. Although protected by wooden boxes, years of dirt, saltpeter, and inattention, rusted and locked all of the press. The move back to the historical headquarters took 10 years. Then came Hurricane María (2017) and added humidity and water, due to the event most of the components necessary to work with the presses didn’t survive.

Returning to the present, Karen Cana-Cruz wanted to relocate the C&P and the Stanhope to an adjacent room, where together they could be both used and exhibited; the C&P had already been loaded onto a dolly. She had purchased, at my suggestion, a hydraulic floor crane on wheels, and Karen’s husband, graphic artist Jose Gabriel Ojeda (Gaby), and I assembled the crane and moved the C&P to its new place and lifted it off the dolly in one piece and set it on the floor. We examined the press and decided how we could proceed to prepare it further for use. Then we rigged the roughly 200lb bed of the Stanhope to the crane and lifted it off, set it on the dolly, and rolled it out of the way.

From left: Paul Moxon, Jose Gabriel Ojeda, Fabio De León, Robert Oldham, and Eric De León (Rocío Tejada López)

With the whole crew participating, we lifted the Stanhope slightly off the floor and moved it, sliding and slipping on the lovely black and white marble stone tile floor, to its chosen location beside the C&P. We turned the bed of the Stanhope upside-down and set to work cleaning the bearing surfaces that support the bed, both in the rails, or ribs and additional support under the platen. We cleaned the ribs next, then applied some 80-90wt gear oil to the surfaces on the bed and the rails, and using the crane carefully turned the bed back over, and installed it on the ribs.

At this point, the main difference between the French Stanhopes and all others raised its head. The French had used ⅜ diameter rope, fastened to winches in brackets on the ends of the bed and wrapped around but not attached to the barrel of the rounce. Someone had installed rope but tried to do it the way leather girts were installed on all other hand presses, by fastening one end of each length of rope to the rounce barrel with a screw. I wanted to return it to the original design, but, without measuring, I assumed both the two pieces were too short, so we tried to find more rope locally, to no avail. When Gaby came back empty-handed we measured the two pieces of rope we had removed, and one was about a meter longer than the other. I found that the longer piece was apparently just long enough to work, so we installed it. The rounce now moves the bed as the manufacturer intended.

We spent some time with Gaby’s belt sander and a fine grit belt removing rust from the Stanhope’s bed, and then obtained some carnauba paste wax and gave the bed several coats to protect it from moisture.

The International Institute of Tropical Forestry, the agency that gave the grant for this work, sent a video crew, who interviewed, filmed, and took notes about the presses, and will be producing a video about the project and the equipment. For that, I set up what little type we had, got Gaby to make some furniture and wooden quoins, and we locked up the type in a chase on the Stanhope and printed it quite successfully for the video camera, proof that a nearly 200-year-old iron hand press that has been through a major hurricane can still print.

First proof on the restored Coisne Stanhope pulled from metal types by Karen Cana-Cruz. (Robert Oldham)

For the C&P, Gaby and I spent some time with the wire brush on my cordless drill, cleaning most of the rust off the ink disc, bed, and platen. Paul used a set of magnetic platen setting gauges to adjust the platen, but the new rollers did not have trucks, and the platen gripper mechanism was missing. He ordered both items and will ship them as soon as possible. So while the press turns over smoothly using the treadle, printing will have to wait a bit longer. Meanwhile, the staff of La Casa del Libro will have to learn how to set type and lock up a forme, and makeready the C&P for printing. Both the Vandercook and the Stanhope can be used for woodcut and linoleum block printing as they are now, though very little furniture and other necessities had survived the hurricane. Paul is developing a list of tools and other needed items.

Notes

- 1 Nameplate a Coisne Stanhope at Moulin à Papier du Livea, Gorges, France. (Andrew Beverly)

- 2 Erik Desmyter informed me that Coisne’s works were located at Rue de la Harpe 97 in Paris. He received a French patent in 1845 for improvements to the Stanhope press, but he ad been manufacturing Stanhopes, and perhaps others, for many years previous. The patent apparently included the replacement of the counterweight to lift the platen by four coiled springs surrounding the screw spindle, an improvement that made Coisne famous.