Monotype’s Obsessions

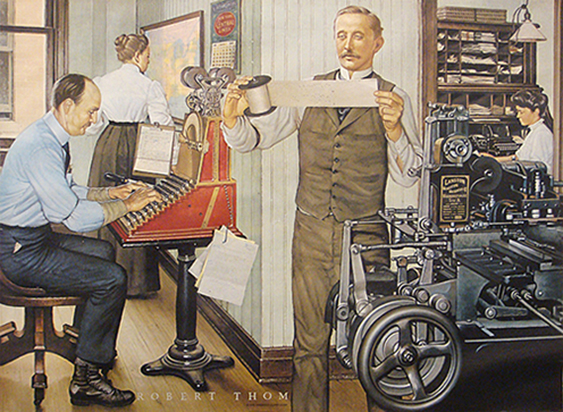

Robert A. Thom, “Tolbert Lanston and the Monotype”, oil on canvas, Kimberly Clark Graphic Communications Through the Ages Series, ca. 1960. Courtesy of RIT Cary Graphic Arts Collection.

In my introduction to my book Tolbert Lanston and the Monotype: The Origin of Digital Typesetting (University of Tampa Press, 2013), I noted that a whole lot of “stuff” was left out of the book intentionally. Paul Moxon has asked me just what that “extra stuff” might be.

Well, the Monotype is a complex piece of equipment with dozens and dozens of specialized, components, which are necessary when doing special work on the machine. For example, the process of changing over from casting American-style matrices to English-style matrices requires a bunch of different components from bridges, centering pins, molds, and so forth. It gets even more complex when the English matrices have been milled down to American standards, for an additional spacer plate must be put under the American mold in order to successfully cast the matrices.

It can be said without fear of challenge that every “rule” regarding the Monotype and its components has several exceptions, and an entire book could have been written on these issues. That, I thought, was outside the realm of the book I set out to write. My major objective was to tell the story of the individuals involved in making the Monotype machine a success. I also wanted to clear up the distinction between English Monotype and American Monotype and in order to do that, I had to get a trifle bit technical on some matters. But most often I skipped over technical details, feeling they would not be pertinent to readers who had no intention of ever running a Monotype machine.

Looking back on my book, if there is one “issue” I feel might have been handled differently, I would say perhaps I should have hit harder on the fact that the Monotype company had to establish standards where there were none, it had to develop machining techniques where there were none, and to a very large extent, the company had to establish huge numbers of jigs, inspections, and technical information in order to make the machine a success. Considering that the human eye can easily detect that a letter is out of alignment as little as the thickness of a human hair, it’s absolutely stunning to realize the company manufactured thousands—even millions—of matrices over the 70 years or more that it was in business. Yet it remained possible up until the end to order replacements made today to fit into a font of mats bought fifty years earlier—and the new mats would still fit in with and align with the older ones.

They were so obsessed with precision, consistency and interchangeability in parts, matrices, etc., they even had to make their own screws and nuts because none could be acquired meeting their tolerances. The whole process of mass producing Monotype machines was on the cutting edge of the development of standards, procedures, and equipment in manufacturing which remain in place even today. That’s quite stunning when you think about it.