From The APHA Letter No. 58, 1984, No. Two:

Before a capacity audience at APHA’s Annual Meeting on January 28, 1984, John Dreyfus was named as the recipient of the APHA Annual Award. A special plaque was presented to Mr. Dreyfus and the following citation was read by J. Ben Lieberman, Chairman of the Nominating Committee: “In recognition of a lifetime career of distinguished service in the interest of printing history specifically, as a scholar, writer, editor, lecturer, consultant, and typographer, the American Printing History Association, by a unanimous vote of its officers and Board of Trustees is honored to bestow upon John Dreyfus of London its 1984 Award, conferring upon him the title of Laureate of the Association. Among the achievements which this award salutes are the following: his role in organizing the important Gutenberg Quincentenary Exhibition in Cambridge and designing its catalog and advertising matter; his service as typographical adviser to Cambridge University Press from 1955 to 1982; as typographical adviser to the Monotype Corporation during the same 1955-1982 period; and European consultant to the Limited Editions Club from 1956 to 1977. In all these he helped infuse the operations with historical perspective as well as direct typographical judgment. His service in type development at the Monotype Corporation includes the Univers series, Dante, Sabon, Mercurius, Pepita, Castellar Titling, and Octavian, among many other typefaces. His part in founding the International Typographical Association was just saluted by a telegram. He served as founding vice president in 1957 and then as president from 1968 to 1973, and is now the honorary president. He organized major international congresses in Prague, London, Copenhagen, and, most recently, the Fifth Working Seminar of A. Typ.I. (Association Typographique Internationale) at Stanford University last year. His service on the editorial and selection committee for the London exhibition in 1963, “Printing and the Mind of Man:’ in addition to designing its catalog. His participation in the Pierpont Morgan Library in 1976, “William Morris and the Art of the Book exhibit, and, additionally, his contribution of an essay to the catalog, ‘~illiam Morris, Typographer.” His chairmanship of the Printing Historical Society from 1975 to 1977 with its tangible contributions, including restructuring of the PHS publication program to ensure production of publications on a regular schedule as well as organizing the Caxton International Congress of 1976, for which occasion he wrote the book William Caxton and His Quincentenary, published in New York and San Francisco; his seminal essay, “Typographical Consequences of the Arts and Crafts Movement Through the Establishment of the Private Press,” published in the exhibition catalog published by the National Book League Art and Work in 1975; his service as editor on the UNESCO International Committee to prepare the International Year of the Book, and Charter of the Book, and as co-editor of Dossier Mise en Page which was awarded the Vox Prize; his participation in many organizations including the presidency of London’s Double Crown Club and membership in the Type Directors’ Club of New York, the Bund der Deutscher Buchkunstler and the Ecole de Lure; and as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and the Institute of Printing, as well as a governor of the London School of Printing, and, finally, his direct spreading of knowledge of printing history through contributions such as the Journal of the Printing Historical Society, The Library, Motif, Penrose Annual, Times Literary Supplement, and Fine Print, as well as lectures before such organizations as the International Federation of Master Printers, London’s Institute of Printing, the St. Bride Printing Library, Stockholm’s Graphic Institute, the Library of Congress, the Newberry Library, the Boston Society of Printers, Philadelphia’s Philobiblon Club, the Pittsburgh Bibliophiles, as well as other groups in many American cities and towns. In substantiation of this award, the officers and trustees have also ordered that a plaque be prepared as a tangible token of their gratitude for his efforts and as a permanent summary acknowledgment of his achievements, these being all the more important because of the role of printing as carrier of the intellectual, cultural, and informational lifeblood that sustains the humane society that England and America share.” The plaque presented to Mr. Drefus reads as follows: “This plaque commemorates the 1984 Annual Laureate Award of the American Printing History Association to John Dreyfus in grateful recognition of his services in advancing understanding of the history of printing and its allied arts.”

The excellent talk by Mr. Dreyfus, recounting his own early experiences with printing history, was enthusiastically received. Members will be pleased to learn that APHA intends to publish Mr. Dreyfus’ talk in its entirety.

From The APHA Letter No. 33, 1980

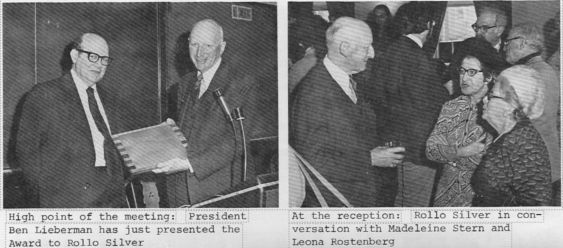

FIFTH ANNUAL APHA AWARD. At the January 26th Annual Meeting of APHA the Fifth Annual APHA Award was presented to Dr. J. Ben Lieberman for his contributions to the study of printing history. APHA President Catherine Brody presented the Award plaque to Dr. Lieberman and read its inscription: “This plaque, the 1980 Annual Award of the American Printing History Association, is presented to J. Ben Lieberman in grateful recognition of his important service advancing understanding of the history of printing and its allied arts.” As Prof. Brody’s presentation talk pointed out, Dr. Lieberman’s contributions to the encouragement of the study of printing have taken many forms. His abiding concern has always been to retain the humanistic values of true printing craftsmanship and preservation of the freedom of the press. Dr. Lieberman founded the American Printing History Association in 1973 to encourage the study of printing history and the preservation of printing artifacts as part of the humanistic tradition. He guided the infant organization in its role of encouraging individuals, institutions and other organizations to contribute to a common goal of preserving and using oral, written and printed source materials for printing history. Dr. Lieberman is a noted private press proprietor at his Herity Press, which he operates with his wife Elizabeth. He has long been active in the Chappel organizations of private presses, having founded the world chappel movement in 1956. The Herity Press was founded in 1952, when the Liebermans lived in San Francisco. It is now located at their home in New Rochelle. Star of their press, pridefully ensconced in their living room is the famous Kelmscott/Goudy press. This Albion was the press used by William Morris’ Kelmscott Press for the Kelmscott Chaucer. Later it was owned by Fred Goudy, the American type designer, and eventually came into the Lieberman printing shop.

Ben’s doctorate is in political science from Stanford. He began his career as a newspaper reporter in his home town of Evansville, Indiana. During World War II he was the Director of Informational Services for the U.S. Navy with the rank of Commander, and editor of the monthly magazine, ALL HANDS. He was professor in the Graduate Schools of Business and Journalism of Columbia, and taught at the University of California at Berkeley. He was consultant to the Ford Foundation’s Fund for the Advancement of Education, worked with the UN’s Organization for Economic Cooperation, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and the U.S. State Department’s foreign aid program. He was a public relations associate at General Food, worked as an economist at Stanford Research Institute, as the assistant general manager of the San Francisco Chronicle. He joined the international public relations firm of Hill and Knowlton in 1967 and became a vice president in 1970. He took early retirement only a few years ago to work on some personal projects.

Major among these was the establishment of the Myriade Press, which has published some valuable books in the field of graphic arts, including such valuable sources as GOUDY’S TYPE DESIGNS H. Zapf’s TYPOGRAPHIC VARIATIONS, and a second edition of Ben’s own valuable TYPE AND TYPEFACES. Ben’s publishing endeavor has done a real service to students of printing in making these books available, in the series he has named the

“Treasures of Typography.”

One of the products of the Herity Press is publication of a “Check-Log” of private press names, compiled by Elizabeth Lieberman. This little book acts as a register of private press names and help private press props. to avoid duplicating a press name already in use. The CHECK-LOG has gone through many editions.

Ben’s book PRINTING AS A HOBBY has been published in both hard cover and paperback and has inspired many an amateur printer.

Ben Lieberman is also an inventor with patents on three different kinds of very simple small printing presses designed for home use. One of the presses, called the Liberty Press, has been bought by more than 10,000 beginners through his own company.

Presenting the Award plaque to Dr. Lieberman, Prof. Brody made the following remarks:

“Through his own extensive writing, through his publishing, through his printing, through his encouragement of private press printing and the chappel movement, but most of all for his ability to inspire all of us with his own ideals we thank Ben Lieberman today. Ben’s indomitable spirit can not be subdued, even by illness. We gave Ben a citation when he stepped down from the APHA presidency in 1978, and I simply want to repeat what we expressed then: ‘For both his indispensable contributions of the past, and the advice and support we shall receive from him in the future, we hereby express our deepest respect and gratitude.’ Ben embodies the very spirit of APHA. For all of his contributions to the study of printing history, I am proud to bestow upon him our Annual APHA Award.”

From The APHA Letter No. 15, January-February, 1977

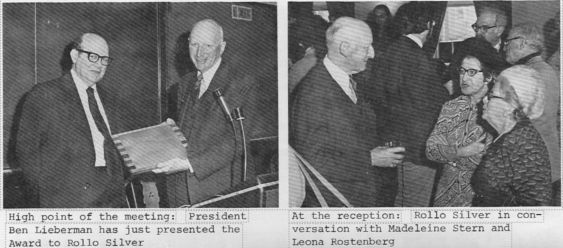

“In grateful recognition of his outstanding lifelong contribution to the.development and understanding of the history of printing, through his painstaking and impeccable research, through his lucid and authoritative authorship of numerous definitive books and even more numerous articles, monographs and lectures, through his leadership in organizations devoted to printing and its historic role, and through his enthusiastic support of other scholars in the field and students he has inspired to serve the cause, Rollo G. Silver is this day, January 29, 1977, presented the 1977 Award of the American Printing History Association by unanimous vote of the Association’s Board of Trustees.”

His laureate address, “Writing the History of American Printing,” provided a broad program for APHA in the area of historical scholarship. The audience’s enthusiastic response indicated how well Prof. Silver crystallized APHA’s goals.

“The History of American Printing seemingly has already been recorded,” he noted, “in the newspapers, books, pamphlets, manuscripts and artifacts scattered throughout the collections in this country and abroad. The information is there. But the point is that we have to organize it.”

“It must be one of our major concerns to find out more about such American geniuses as Samuel Nelson Dickinson,” Prof. Silver emphasized, in describing some of Dickinson’s wide-ranging and important (but too little known) activities. Other specific projects he suggested were the compilation of lists of printing presses with descriptions and details of their manufacture, a series of exact reproductions of early American type specimens; updating of bibliographies on printing history; study of local archival records of printing concerns; and inventories of presses and other equipment of every printing shop in a given town or neighborhood.

Prof. Silver advised printing historians to forget about the Colonial printer for now, and concentrate instead on the technical developments of the 19th century. To do this, it will be necessary for historians to work closely with engineers, he pointed out. APHA can foster such cooperation, and can help the scholar in other ways, settling for nothing less than the highest standards. Full documentation should be insisted upon, he remarked; “let the policy be, ‘all the footnotes fit to print.'” APHA should similarly encourage joint efforts with art historians in recording and analyzing the aesthetics of printing and the various styles. “Printers who recognized and worked with the best of current trends (of art) … deserve a place in our history.” Prof. Silver summarized his recommendations by remarking that “with scholars and technicians working together, and with all the necessary footnotes, the history of American printing can be organized.” APHA hopes to be able to publish Prof. Silver’s address in full and distribute it to the entire membership.

APHA presented its Individual Award posthumously to Hugh Amory, retired Senior Cataloger in the Houghton Library, on January 26, 2002. Hugh’s son Patrick received the citation from David Whitesell of the Awards Committee, and a tribute was offered by Roger Stoddard, Curator of Rare Books, Harvard College Library.

“For Hugh from Roger at APHA, 26 January 2002”

Speech of Roger Stoddard, Harvard University Library, in honor of Hugh Armory (1930–2001)

Good afternoon! It’s been six years since you invited me and David Whitesell to speak about books and Thomas Jefferson. David’s paper, altogether brilliant and far more original than mine, remains unpublished; but you printed mine, so you know that I quoted Hugh Amory on the unreliability of printer assignment in early American books: “incomplete, inconsistent, and unreliable,” he said. Since then Hugh and I have lamented jointly the identical situation in English books, 1641-1700. Fortunate are the members of APHA to have such open and fascinating fields for research. If only Hugh were here with us this afternoon so that I could roast him, what fun we would have! What laughter! What a life! Well, here we go, Hugh:

As he was general and unconfined in his studies, he cannot be considered as master of any one particular science; but he had accumulated a vast and various collection of learning and knowledge, which was so arranged in his mind, as to be ever in readiness to be brought forth. But his superiority over other learnèd men consisted chiefly in what may be called the art of thinking, the art of using his mind: a certain continual power of seizing the useful substance of all that he knew, and exhibiting it in a clear and forcible manner; so that knowledge, which we often see to be no better than lumber in men of dull understanding, was, in him, true, evident, and actual wisdom. … Though usually grave, and even aweful in his deportment, he possessed uncommon and peculiar powers of wit and humour; he frequently indulged himself in colloquial pleasantry; and the heartiest merriment was often enjoyed in his company; with this great advantage, that as it was entirely free from any poisonous tincture of vice or impiety, it was salutary to those who shared in it. [James Boswell, Life of Johnson, ed. R. W. Chapman (Oxford University Press, © 1980), pp. 1400-01.]

You will recognize these sentiments as those of James Boswell in his summary of the character of Samuel Johnson, but for those of us who were his colleagues, these words apply just as well to:

Hugh Amory

(July 1, 1930-November 21, 2001)

In his youth Hugh was mechanical, assembling parts in order to achieve special effects. He designed and constructed a cart for his brothers, he mastered the soldering iron, he cast lead soldiers, he cast wax soldiers, he learned how to concoct gunpowder. (Later, in Korea, he served as staff sergeant in the U. S. Army Explosive Demolition Team.) He taught himself how to take apart the engine of his Cord automobile and how to put it back together again: it worked just fine. All of it worked just fine–except for the wax soldiers; they emulsified with cauterizing effect.

At Harvard he discovered the Poet’s Theatre–more special effects–for which he composed at least two vehicles, one of them being a translation of Sophocles’s Ajax. He got a reputation as a poet. The sublime Frank O’Hara challenged him:

Listen, you mad poet, never

ask for gasoline from the girl

selling bonbons in the department store!

…

Your words, sea-rushed engines,

hammer on, and from the muck

and bones and golden curls and silk

your sienna house, New Jerusalem,

rises. Art! Hosanna! Huzzah!

[Frank O’Hara, Early Writing, ed. Donald Allen

(Bolinas, CA: Grey Fox Press, © 1970), p. 64.]

After achieving the magna, with highest honors, in 1952, he styled himself “playwright” in his class report, but in 1958 he got the LL. B. from the Law School, followed by the Ph. D. in English literature–eighteenth-century, he would report, from Columbia in 1964. There they charged him with the proseminar as Assistant Professor, and his former student and later colleague and collaborator Elizabeth Falsey recalls him as smart, mysterious, infuriating. Student papers were followed by an hour and a half of punishing cross examination, and the material argument or material evidence seemed to be a subtext. They asked themselves Where was he coming from? Didn’t they know that the protocols of the classical rhetoric of Quintilian together with courtroom practice and the handling of evidence would follow a law school graduate into any classroom? Only years later did Elizabeth figure out that Hugh had been teaching from the perspective of a library, the attitude of a library cataloger.

But where were the publications of smart young Hugh Amory? Just an eight-page article in the journal of the Manuscript Society, and that just a touch-up of his classroom handout, “Eighteenth Century Autographs and Manuscripts: a Selective Bibliography”? He left Columbia to become an associate professor at Case Western Reserve from 1968 until 1973. But where …

But then, in 1972, the tragic death of Daniel E. Whitten opened a position for a cataloger in English literature at Houghton Library. Hugh came for interview on a Saturday, so James Walsh, Keeper of Printed Books, had to unlock the great front door of the library for him, locking it up behind him with the usual great thud and echo. Must have seemed like the Tombs–or a Yale fraternity house! James handed him two copies of an early English book. They were the same (line-for-line), but also different, as one was a reprint of the other. There was no reason for Hugh to spot the differences so fast and explain them so well, for, whatever he had been doing, he hadnot been comparing dozens or hundreds of early printed books in order to sort out bibliographical conditions. James was dumbfounded, Hugh got the job and remained inside the great front door. Hugh Amory, the catalog department, and Houghton Library were never the same again.

My first clear recollection of him is the moment when he discovered me unpacking from two tea chests the Russian books that I had bought at the Diaghilev-Lifar sale at Monaco in 1975. He seemed reluctant to believe what he was being handed, including all those gift books and journals with printed labels from the Paris exhibition that Lifar had organized for the Pushkin centennial in 1937, and that Hugh would organize and publish for Houghton’s celebration of Pushkin’s 150th in 1987. How was I to know that he could read the stuff?

That compartment behind the great front door was no sleeping car, it was an express special into print for Hugh, beginning with a prodigious output of catalog cards. Neither language nor subject could baffle him, and he would explain to you that he had simply changed classrooms, for he was teaching as before; books remained his subject, but catalog descriptions were his lectures.

That was not enough for him, for someone who wanted to create special effects. One thing to describe a book, another to show it. From 1977, with his Edward Gibbon, Hugh became the library’s most prolific and inventive designer of exhibitions: Johnson, Mather, Fielding, Pushkin, F. J. Child, Cambridge Press, Carlo Goldoni. Many were memorialized by printed catalogues no less creative than the shows that spawned them: He Has Long Outlived His Century (a catalogue written by Harvard graduate students for the Johnsonians), New Books by Fielding (designed for class reading, just like Pushkin and his Friends), The Virgin and the Witch(poster/catalogue of the Law Library exhibition on Elizabeth Canning),First Impressions: Printing in Cambridge (distributed with the long-awaited type specimen of the press). He changed formats, won prizes, reformatted the exhibition cases. Articles flowed freely now, rich with insights and connections, full of new data from unexpected sources. All the while, Fielding provided the ground bass; is any English author so well ‘grounded’ in every aspect of printing, bookselling, and reading culture now that Hugh has considered and recorded all those aspects with his articles and editions?

At his retirement party Hugh shared an important anecdote. He said that cataloging books was not very difficult, in fact it was easy, just telling the truth about books. But recently he had discovered that the authorized heading for Ossian, the fictitious creation of James Macpherson, was “Ossian, 3rd cent.” as if such a person had actually existed. He complained to the LC authority office, but he was told to subside–the heading holds false to this day: they had created it by analogy with the heading for Homer. “So, I’m glad I’m retiring. Now I can go back to telling the truth about books,” he concluded. And so he did.

Almost immediately appeared the indexed facsimiles of the first three catalogues of the Harvard Library, then five years later The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World, both of them monumental contributions to American history from the point of view of The Book. The first was a collaboration with W. H. Bond; Hugh helped to identify the “cataloged” books, but also he rendered the badly printed originals, with the readthrough that had prevented any earlier facsimile edition, into legible masters, no mean feat. He collaborated in the editing of the latter with David Hall; instead of thinking about what he contributed–all the sections are signed, just consider what the volume would have been without his knowledge of British booktrade practice and without his clearheaded analysis of printing statistics. Don’t just count the products, he said, distinguish job printing from newspapers and book printing; count by the energy factor of the press, materials plus labor, by enumerating sheets, just as the trade priced their work–by the sheet. Don’t miss his “Pseudodoxia Bibliographica [i.e., False Bibliographics], or When is a Book not a Book? When it’s a Record” in the Consortium of European Research Libraries Papers II: The Scholar & The Database (2001).

Hugh’s colleague, the Slavic cataloger Golda Steinberg, would burst into tears when she saw how the cancer was ravaging his body and darkening his countenance. We embraced, Golda and I, when word of his death reached the library. She says that she still sees him, don’t we all, with his face deep in a book, concealing for the moment that outrageous laugh of his that so endeared him to friends!

The next issue of The Book, newsletter of the Program in the History of the Book, will memorialize Hugh by printing work both by and about him. His chapter on the London booktrade will appear in the fifth volume of The History of the Book in Britain, and his biography of Andrew Millar will be printed in the New Dictionary of National Biography. Let us hope that we will see more fruits of Hugh’s dedication to the products of the printer’s twenty-six little lead soldiers, as he styled them. What a life! What an afterlife! What laughter! What special effects! What fun we had!

Roger Stoddard

Curator of Rare Books, Harvard College Library

Posted with the author’s permission. Copyright remains with the author.