Good, But Not So Fast or Cheap

The following paper was intended to be the keynote address at the APHA/CHAViC Conference. While Dr. Winship was unable to deliver it, the American Printing History Association is pleased that he has allowed us to present it here.

The following paper was intended to be the keynote address at the APHA/CHAViC Conference. While Dr. Winship was unable to deliver it, the American Printing History Association is pleased that he has allowed us to present it here.

It has become a commonplace to associate the industrial revolution in the United States with the emergence of a mass culture aimed at a popular and commercial marketplace and to characterize the output of American printers and publishers of the industrial era with such adjectives as “good, fast, and cheap.” Many accounts echo this assessment, pointing to a supposed “century-long quest to make books more quickly, more cheaply, and in greater numbers than ever before.”1 If not exactly pejorative, such assessments do not hold much promise for the connoisseur of high-quality fine printing.

There can be little doubt that these characterizations of American industrial book production reflect in large part the major shift in aesthetic taste that occurred during the final decades of the nineteenth-century in reaction to what was believed to have been a loss of aesthetic sensibility as industrialization changed the organization and technologies of manufacture. The writings of John Ruskin pointed the way, and we see this new sensibility reflected in the books produced under the influence of the aesthetic movements of medievalism, japonisme, fin-de-siècle decadence, and neo-classicism in England by William Morris, J.A.M. Whistler, Aubrey Beardsley, T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, among others. These British works were imported and noticed in the United States, and these new styles were adopted at the end of the century in works issued not only by boutique publishers like Copeland & Day in Boston, Way & Williams in New York, or Stone, Kimball & Co. of Chicago, but also by those from many of the long-established trade houses in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.2

Perhaps the most clearly articulated statement of this changed attitude is that of Theodore L. De Vinne in an article entitled “Masculine Printing,” first delivered to the United Typothetæ in 1892, printed in that society’s proceedings, and soon reprinted in the American Bookmaker for a wider audience.3 The piece begins by proclaiming: “today we make use of two distinct styles or printing, which … can be best defined by the adjectives of masculine and feminine.” Masculine printing, according to De Vinne, is “noticeable for its readability, for its strength and absence of useless ornament” and far to be preferred. Among masculine printing’s characteristics, he notes, are “black ink,” “firm impression,” and “well made paper,” all of which helps make the work “readable by its simplicity and its honest workmanship.” Feminine printing, in contrast, is “noticeable for its delicacy, and for the weakness which always accompanies delicacy, as well as for its profusion of ornament.” It is the result of “Sharp and almost invisible hair lines, under inked with hard rollers, and printed by feeble impression on dry, super-calendered paper” taken to be “evidences of the highest workmanship.” He goes on to explain: “My contention is that too much of what we call ornamental printing is not ornamental at all.”

Far be it from me to wade into the gender politics that form the basis of De Vinne’s characterization of the printing of his time.4 Clearly, most would never use such gendered terms today, nor am I convinced that ornament and delicacy are, of themselves, necessarily something to avoid. Nevertheless, one must take De Vinne’s opinion seriously. After all, he was himself an accomplished, practicing printer, who published widely on typography and best printing practices, as well as the early history of printing in Europe. Furthermore, he was a founding member of both the New York Typothetæ and the Grolier Club, and received honorary degrees from both Columbia and Yale Universities.5 But still, as recent events have made abundantly clear, silently accepting the dominance of the patriarchy as the status quo or claiming the superiority of “masculine printing” without question can no longer be acceptable.

In this talk, I propose to survey examples of fine printing from the early years of the American industrial book—say from 1825 to 1880—emphasizing the ways American printers and publishers used the new technologies of production made available by industrialization to produce work that reflected both excellence in manufacture and aesthetic appeal. A major goal of my talk is to reexamine these works from a fresh perspective, one that attempts to encourage us to remove the filter that the assumptions and prejudices that William Morris, his followers, and others from the Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movements at the end of the century have placed between us and these works.

I am certainly not the first to point to the appeal of these works. The late Sue Allen and her students have long appreciated the design appeal of the cloth covers of many American publishers’ bindings from the nineteenth-century. Art historians, perhaps to a lesser extent, have recognized the excellence of illustration from the period by American artists such as F.O.C. Darley, Mary Hallock Foote, Winslow Homer, and Augustus Hoppin—we await eagerly the study of illustrated literary works that is being prepared by Gigi Barnhill. Others have focused on the extravagance exhibited by skilled job printers working with ornamental types and rules during the 1870s and 1880s. But few have recognized the skills of the book printers and taste of the trade publishers to be found in many books produced during this period. Printing establishments such as the Riverside and University Presses of Cambridge or C.A. Alvord of New York were capable of skillful presswork that later firms would be hard put to duplicate, especially in integrating text and illustration, and major publishers such as D. Appleton & Co., Harper & Brothers, G.P. Putnam & Co., and Ticknor and Fields oversaw and financed the creation of many volumes that still seem remarkable today. It is this “good, but not so fast or cheap” world of American printing and book production that I want to explore as a first step toward recovering a more complete history of American fine printing during the industrial era.

Many of the works that this talk examines are those that have stood out to me over my long career as their bibliographer and historian. It has often struck me that, in general, they have been mostly ignored or overlooked because they reflect that Victorian aesthetic disparaged by De Vinne, not to mention William Morris and his contemporaries. I cannot promise to change your own aesthetic sensibilities—no accounting for taste, after all—but I still hope to convince you that you will find it worth your while to give these books another look and to make the attempt to appreciate them on their own terms.

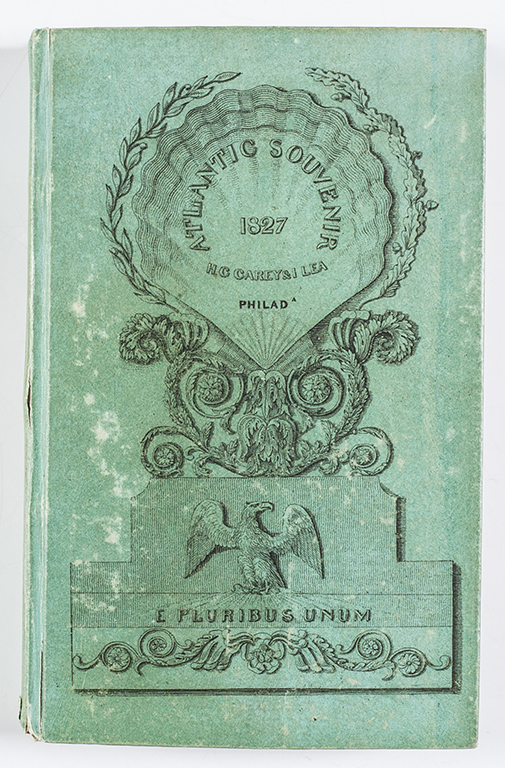

Fig. 1: The Atlantic Souvenir for 1826, 1827, and 1828. (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 246798, 246799, & 246801)

I begin with the Atlantic Souvenir, published by Carey & Lea in Philadelphia, first in late 1825 and then annually until 1832, when it was sold to S.G. Goodrich and his backers to be merged with The Token of Boston [figure 1]. It must stand for the many hundreds of literary annuals that were published as gift books in the United States during the antebellum years.6 As a genre, the literary annual, designed to serve as a gift during the Christmas and New Year’s season, had originated in Europe a few years earlier, then was copied in London before appearing across the Atlantic. Elaborately printed and bound, illustrated by inserted engravings, the best of them represent the potential for a new aesthetic for printing made possible by new, industrial methods of book production. Dainty and small, printed on machine-made paper with a small modern typeface, they stand in stark contrast to the large paper, wide margins, and excessive leading that one finds in the work of Bodoni or Baskerville so sought after by collectors only a generation earlier. The ornamental bindings, in paper, leather, and later cloth, were early examples of publisher’s bindings, and it is hardly surprising that the earliest surviving examples of dust wrappers and slipcases belong to these books.

The historian Stephen Nissenbaum has argued that these literary annuals “were the very first commercial products of any sort that were manufactured specifically, and solely, for the purpose of being given away by the purchaser.” “In a sense,” he points out, “Gift Books picked up where almanacs left off” just at a time when more and more Americans were ordering their lives by the clock, as called for by industrialization, rather than the traditional rhythms set by the sun, moon, and seasons recorded in almanacs.7

Fig. 2: The Atlantic Souvenir for 1827. (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 246799)

The Atlantic Souvenir was the first of the American gift books, though others quickly followed. It was expensive: the first in the series was produced in late 1825 in an edition of two or three thousand copies at the cost of a $1.67 each and sold at a retail price of $2.50, but was distributed to the trade at a discount of one third. It was printed on machine-made paper from the Gilpin mill in Wilmington, Delaware, which cost $8 per ream, nearly double the cost of equivalent hand-made paper, and the cost of binding came to an extravagant 36¢ per copy. It was popular: during the 1830s over ten thousand or more copies were produced each year at a cost of over twelve thousand dollars each. It was also a patriotic endeavor: all of the contributors were American, as were the engravers and most of the images—paintings or new designs—that they reproduced [figure 2]. Over the course of its publication, the Atlantic Souvenir printed contributions, many appearing anonymously, by William Cullen Bryant, Lydia Maria Child, Washington Irving, James Kirke Paulding, and Catharine Maria Sedgwick, many of the authors recognized today as playing a role in establishing a distinctive American literary culture.8

The Atlantic Souvenir and other literary annuals, printed on machine-made paper and issued in publisher’s bindings, were quintessentially products of the early years of the industrialization of book production, so it is no surprise that these early volumes coincide with the emergence of the national book trade publishing system that has characterized trade publishing in the United States during the industrial era. Henry Charles Carey and Isaac Lea, publishers of the Atlantic Souvenir, were the son and son-in-law, respectively, of the important pioneering Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey, who himself had only recently retired from the firm. H.C. Carey was to play an important, perhaps less widely recognized, role in the emergence of the trade publishing system in America. Only months before the first in the series of the Atlantic Souvenir was issued, the younger Carey had organized the first American book trade sale. These were auction sales, strictly limited to members of the book trade, that served not merely as a way of distributing publications to the emerging and expanding national market, but also played a vital role in managing financial relations and regulating behavior within the trade, especially in the antebellum years when the trade system was becoming established. Also during these years, the Carey firm initiated the practice of printing new works, such as the novels of James Fennimore Cooper, directly from stereotype plates from the very first, another feature that became a characteristic of American publishing during the industrial era.9

In these same years, another firm, J. & J. Harper, but soon to become Harper & Bros., was coming into prominence. Starting out as printers rather than publishers, they made a specialty of producing inexpensive American reprints of British works, especially novels, and one does not usually associate the firm with distinguished typography. Nevertheless, certain of their publications deserve notice. I think of The Fairy-Book, a children’s book first issued in 1837 and illustrated with charming chapter heads and ornamental initials, “cuts in wood” by Joseph Alexander Adams, or William Hickling Prescott’s History of the Conquest of Mexico of 1843, a large octavo in three volumes with a straightforward and understated, but I think still rather elegant, typographical presentation that easily accommodated Prescott’s sometimes lengthy footnotes.10

Fig. 3: Harper’s Illuminated and New Pictorial Bible (New York: Harper & Bros., 1843). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 146870)

One Harper publication stands out: Harper’s Illuminated and New Pictorial Bible, published serially in fifty-four numbers, by subscription, from 1844 to 1846. The completed volume was “embellished by sixteen hundred historical engravings, exclusive an ornamental initial to each chapter, by J.A. Adams, more than fourteen hundred of which are from original designs, by J.G. Chapman” [figure 3]. It was a decided success and, in 1858, it is reported that 25,000 copies had been sold. In order to allow so many copies to be produced, Adams worked with the Harpers to perfect the electrotyping process for reproducing the many embellishments and ornaments to good effect. As the editor to the New York Courier and Enquirer noted, “Many of the illustrations of this work have been repeatedly mistaken by persons of the most accurate taste for the most highly-finished steel engravings; and their superiority to copper-plate is universally acknowledged.” In sum, he concludes “the whole typographical appearance of the book gives it rank as by all odds the most magnificent production of the publishing art in the United States.”11

Fig. 4: James Kirke Paulding, A Christmas Gift from Fairy Land (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1838). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 409455)

Another publishing firm that emerged during these early years of the industrial era also issued some remarkable books. Daniel Appleton began in business in Haverhill then Boston with a wholesale dry goods store, but after moving to New York in 1825 and entering a partnership with his brother-in-law, Jonathan Leavitt, he added bookselling to his business. By mid-century, D. Appleton & Co. had become a major publisher and player in the book trade, but bookselling, both retail and wholesale, especially of books imported from Britain, remained a major, if not the major, part of the business.12 In 1838 the firm issued James Kirke’s Paulding’s A Gift for Christmas from Fairy Land, a retelling of fairy tales illustrated by many delicate vignettes incorporated into the letterpress text as well as inserted engravings printed in pale blue, green, red, or brown ink [figure 4]. This was certainly a gift book, but quite distinct from the literary annuals discussed earlier—indeed, I know of no other American book quite like it.

One final publisher from this period, George Palmer Putnam, was instrumental shaping the emerging national book trade system of the United States during the antebellum years. During the 1830s, working for Jonathan Leavitt as a young clerk at Leavitt, Lord & Co., he edited the first American book trade journal, The Booksellers’ Advertiser and Monthly Register of New Publications, and produced an early attempt to make a record of all books available for sale in New York City, something like our modern Books in Print. Both efforts were premature. The Booksellers’ Advertiser lasted a single year, but its purpose was picked up again during the following decade by Wiley & Putnam’s Literary News Letter, which arguably was to grow and evolve over the years to become our current Publishers’ Weekly. Also during the 1840s, Putnam managed the Wiley & Putnam firm’s London “literary agency” and, while living in England, became an important agent for introducing American books to English readers and major supporter of international copyright legislation.13

Fig. 5: Homes of American Authors (New York: G.P. Putnam & Co., 1853).(Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 462415)

Though never as successful financially as the Harpers or Appleton, Putnam did play an influential role as a publisher and was responsible for the publication of many important American literary works from this period, including those by Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Edgar Allan Poe. I would like to point to several. In 1853, G.P. Putnam & Co. published The Homes of American Authors, a collection of “anecdotal, personal and descriptive sketches” about the residences and domestic lives of many important contemporary writers [figure 5]. Much remains to be worked out about this work’s many variants or bibliographical history, as well as the identity of the authors who contributed the various sketches, but it is a remarkable example of American bookmaking of the period. Each sketch is accompanied by an inserted facsimile of a manuscript by the author and many by an inserted steel engraved portrait or view of the residence. Just as many are illustrated on text pages by wood engraved sketches, printed in colors from multiple blocks, usually of landscapes. In some copies, as here, these are printed on tissue, then tipped into the volume, in others printed directly on the printed sheets with text. The overall effect, I think, is quite charming. A companion volume, The Homes of American Statesmen, stands as the first American book illustrated by a photograph, a salt print of the Hancock house in Boston mounted as frontispiece.

Fig. 6: Washington Irving, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon Gent. – Artist’s Edition (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1864). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 196583)

Ten years later, in 1864, Putnam published an “Artist’s Edition” of the revised text of Washington Irving’s classic Sketch Book by Geoffrey Crayon, the collection that included, among many others, his tales “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” [figure 6]. In the “Publisher’s Preface,” dated September 1863, Putnam writes that this “special presentation” of the work “has aimed at a high standard of excellence” and that “unusual care has been taken, and unusual cost incurred, as regards the designs, the engraving, the paper, and the printing.” It is illustrated by one hundred and twenty engravings on wood “from original designs by many of our most eminent artists who have taken a warm interest in this experiment.” Furthermore, “The paper has been made for this special purpose with peculiar care, and from the choicest materials’ and the printing, by Mr. Alvord tells it own story to the adept and to the amateur. The binding, by Mr. Matthews, will by appreciated by discriminating lovers of choice books.”

Fig. 7: William Cullen Bryant, A Forest Hymn (New York: W.A. Townsend & Co., ©1860). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 140606)

C.A. Alvord, the printer of this work, was responsible for another remarkable book, which had been published in New York by W.A. Townsend & Co. a few years earlier, a separately reprinted edition of William Cullen Bryant’s single poem A Forest Hymn (1860) illustrated with wood engravings after designs by John Augustus Hows [figure 7]. This style of gift book—a single poem reprinted with wood-engraved illustrations that are printed with the text—is quite different from that of the literary annuals that I began with. As we shall see, it came to predominate as the fashionable style for gift books in the years following the Civil War, just as the taste for those literary annuals faded. The ability to integrate illustration and text and, in many cases, reproduce them in a single pressrun seems to be a particular skill that was developed by American printing firms and a distinctive feature of American gift books published during those years.

W.A. Townsend, & Co., the publisher of A Forest Hymn, was taken over by James G. Gregory early in 1861, and in January 1865 Gregory, before retiring from the trade, sold the plates of this and others of his works to another New York firm, Hurd & Houghton, which had started in the publishing business only the preceding March.14 In addition to continuing to issue Bryant’s poem in this gift book edition over its own imprint, Hurd & Houghton also made arrangements with G.P. Putnam to take over “the exclusive manufacture and sale of his books.”15 This included the “Artist’s Edition” of Irving’s Sketch Book, and in the fall of 1864, Hurd & Houghton reissued this illustrated edition of the Sketch Book in a second, small edition of 500 copies for the holiday season. It included a new “Publisher’s Note,” now dated August 1864, that explained in part that because “the small edition of the book prepared for last season, was quickly exhausted by the eager demand” that an “entirely new impression of the book is now presented, and in this, some twenty additional vignettes will render it somewhat better worthy of the favor it has received.”16

The Houghton of Hurd & Houghton was hardly new to the book trade, however. He was Henry Oscar Houghton, who at the time was more widely known as the proprietor of the Riverside Press of Cambridge, Massachusetts. A native of Vermont, he had started in the trade in 1836 as an apprentice at the Burlington Free Press and would go on to become the primary partner of the important Boston publishing firm, Houghton Mifflin & Co. It is not clear whether either of the two works taken over from other firms in 1864 by Hurd & Houghton were ever printed at the Riverside Press—both still reproduce the printer’s imprint of C.A. Alvord on the copyright page—but the Riverside Press was widely recognized for the high quality of its output even during these years, although today we tend to remember it for the excellence of its work from later years. Both Daniel Berkeley Updike and Bruce Rogers worked at Riverside early in their careers, and their influence on the design of books produced there during the 1890s and early decades of the twentieth century is well documented.

Fig. 8: Poetry of the Bells, ed. Samuel Batchelder, Jr. (Cambridge, MA: Ptd by H.O. Houghton & Co., 1858). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 56974)

I cannot neglect to present at least one work manufactured at the Riverside Press during earlier years. Poetry of the Bells of 1858 was a collection edited by Samuel Batchelder, Jr. and printed at Riverside “in aid of the Cambridge Chime” [figure 8]. Every poem, in one way or another, celebrates bells, in all their variety, and the book includes contributions from Cambridge residents Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell among those by many others from elsewhere, including Edgar Allan Poe, who is represented (I suppose inevitably) by his popular earworm, “The Bells.” The text of each page is contained within an ornamental frame made up of delicate type ornaments, and the text itself is printed in an “old style” typeface that had only been introduced and become popular a few years earlier. Modern readers are often surprised to see this mid-nineteenth-century use of the long “s,” ( ſ ) something that we usually associate with early modern printing, but not as a feature of industrial printing. The overall effect of the typography I, at least, find delightful.

But it is another Cambridge printing firm whose work I would like to focus on for the remainder of this talk—Welch, Bigelow & Co., which used the imprint of the “University Press.” Founded in 1859, the firm remained in business for twenty years and over that period was responsible for the manufacture a remarkable series of books published by the Boston’s Ticknor and Fields and its successors Fields, Osgood and Co. and J.R. Osgood & Co. In 1879, Welch, Bigelow & Co. was purchased by John Wilson & Son, which took over the imprint of the “University Press” and continued the tradition of excellence in printing and design.17 Welch, Bigelow & Co. is not as widely recognized as it should be today for the excellence of its work, especially for its skill at printing wood engravings, often integrated with text on the same page. Some enterprising scholar should undertake a full study of the firm and its output.

I start with several books published in 1864, the same year that G.P. Putnam had first issued the “artist’s edition” of Irving’s The Sketch Book. It is a puzzle why so many examples of American fine printing appeared during the final years of the Civil War—the outcome of the war could hardly have been assured at that point, but the book trade must have been thriving.18

Fig. 9: George Ticknor, Life of William Hickling Prescott (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 63848)

George Ticknor’s Life of William Hickling Prescott published by Ticknor and Fields is particularly notable [figure 9]. First advertised in December 1863, just in time for the holiday season, at $7.50, it is described as:

… printed on superfine paper on superfine toned paper, and beautifully bound in vellum cloth, gilt top, and stamped with appropriate designs. In point of view of mechanical execution, it is one of the most sumptuous volumes ever issued from the American press.19

The editors of the American Literary Gazette agreed. In a short notice published the following month, they report:

It is, in all of its departments, one of the most exquisite specimens of book-making, which we have ever had the pleasure of handling. Paper, type, illustrations, and binding are perfect, and the entire volume is a triumph of American artistic skill.20

In 1866 the firm produced an even more sumptuous large-paper printing of this work, limited to 100 copies, with initial letters printed in colors, but earlier, in May 1864, after resetting the text in a more conventional style Ticknor and Fields published the Prescott biography in a “Popular Edition” at $2.00 and an “Library Edition” at a dollar more.

Fig. 10: Edward L. Clark, Daleth or the Homestead of the Nations (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1864). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 37306)

In the spring of 1864, Ticknor and Fields issued another remarkable book produced at Welch, Bigelow: Edward L. Clark’s Daleth or the Homestead of Nations Egypt Illustrated [figure 10]. Priced at $5.00, the page layout is less complicated than that in Ticknor’s Life of … Prescott, and the old-style type eschews such niceties as the long “s” and old-fashioned ligatures used there, but the ornamentation and many vignettes give the book a similar charm. The inserted chromolithographic plates produced by the Boston firm of J.H. Bufford are a special feature.

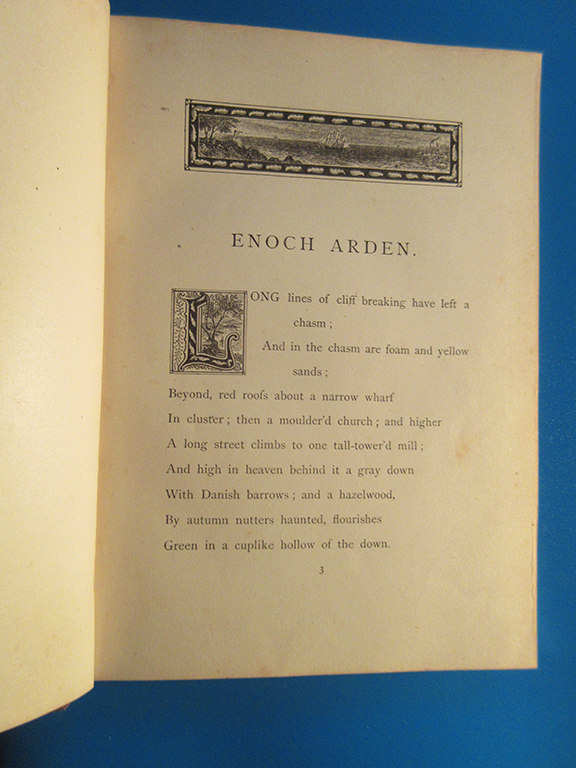

Fig. 11: Alfred Tennyson, Enoch Arden (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1965). (From the collection of the author)

An edition of Alfred Tennyson’s Enoch Arden issued for the holiday season in December 1864 for $2.00 echoes the style that we have seen earlier in Bryant’s A Forest Hymn produced by C.A. Alvord right before the Civil War [figure 11]. It is, however, perhaps even more lavishly illustrated, as it has a portrait frontispiece and vignette of Tennyson’s residence, both printed from steel engravings, as well as nineteen full-page wood engravings made from the designs of John La Farge, Elihu Vedder, W.J. Hennesey, and F.O.C. Darley. The cloth binding is also substantial, with beveled boards and all edges gilt.

Fig. 12: Illuminated and typographic title pages from James Russell Lowell, The Courtin’ (Boston: James R. Osgood & Co., 1874). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 197700)

This style of holiday gift book—a familiar single poem, illustrated lavishly and reprinted separately—would become a feature of Welch, Bigelow & Co.’s work through the 1870s. There are many fine examples that I could choose, but I will limit myself to only a couple from that decade. The separate edition of James Russell Lowell’s poem The Courtin’, illustrated “in silhouette” by Winslow Homer, was originally promised for the 1872–73 holiday season, but did not actually appear until November 1873 [figure 12].21 The published volume, printed on rectos only throughout, contains seven striking silhouette illustrations by Homer, reproduced by heliotype and each on its own leaf, which was preceded by an appropriate quote to serve as caption, printed on its own leaf, and followed by a third leaf with the text of Lowell’s poem printed within a red-rule frame. These were the early years of the photo-mechanical reproduction of images, and James R. Osgood, who had in 1871 had become the leading partner in the firm that had once been Ticknor and Fields, had formed a separate company, the Chemical Engraving Company to exploit this development. In 1872 he had leased the rights for the exclusive use of the heliotype process in the six New England states from a London firm, Gilbert & Rivington.22 Complications related to these developments may have contributed to the year’s delay in publication of this book.

Fig. 13: John Greenleaf Whittier, Mabel Martin A Harvest Idyl (Boston: James R. Osgood & Co., 1876). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 203293)

The price of The Courtin’ was $3.00, which was something of a bargain compared to the gift-book edition of John Greenleaf Whittier’s Mabel Martin, which appeared two years later [figure 13]. Advertised by James R. Osgood & Co. as “the holiday book of the year” and “just ready” in Publishers’ Weekly on 23 October 1875, the cost for cloth copies of Whittier’s poem in the “beautifully ornamental cover, and full gilt” was $5.00, for those in morocco leather, $10.00.23 The wood engravings in this book are far more numerous than in the earlier book—there are fifty-eight in all—and include vignettes, headpieces, and illustrations. These were made from designs created by many of the best illustrators of the day—including Mary Hallock Foote, Thomas Moran, Alfred R. Waud, among others—and were engraved by A.V.S. Anthony, under whose “supervision” the book was prepared. Anthony also served as treasurer of Osgood’s Chemical Engraving Company and was regularly involved in the preparation of the fancy gift books published by Osgood and produced at Welch, Bigelow & Co.

Fig. 14: The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans, ed. James B. Longacre & James Herring (New York: Monson Bancroft & others, 1834-1839). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 237217)

Fig. 15 Charles Sumner, White Slavery in the Barbary States (Boston, John P. Jewett & Co. 1853). (From the collection of the author)

With this limited sampling of some of what have struck me as some of the finest books produced by American printers and publishers during the early decades of the industrial era, I bring this survey to a close. There are others well worth considering that occur to me. I think, for example, of The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans, “conducted” by James Herring of New York and James B. Longacre of Philadelphia, under the “superintendence” of the American Academy of Fine Arts. Like the Harper illuminated Bible, it was published by subscription, but with a wide variety of firms listed in the imprint, and appeared first in monthly parts between 1833 and 1839 but then in four bound volumes [figure 14]. Or, the attractive new edition of Charles Sumner’s study of White Slavery in the Barbary States, with numerous illustrations by Hammatt Billings, published in 1853 by John P. Jewett & Co., the firm that the preceding year had published the blockbuster Uncle Tom’s Cabin [figure 15]. There are also the many of works published or printed by Joel Munsell in Albany, New York, during these years.24 Munsell made a specialty of producing works of particular interest to antiquarians and local historians, as in Reuben A. Guild’s The Librarian’s Manual, published in New York by Charles B. Norton in 1858 [figure 16]. But you will have your own favorites that I have overlooked, and I look forward to learning of them. And there are surely others that remain to be recognized. But I trust that we can all agree that many of these works are worth noticing, preserving, and treasuring. Can we not agree that the slogan “good, fast, cheap” does not adequately describe the entire output of American publishers and printers during these early years of the industrial era?

Fig. 16: Reuben A. Guild, The Librarian’s Manual (New York: Charles B. Norton, 1858). (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, ID 44672)

Notes

- 1 Elizabeth Ott, Turning the Page: Technology & Innovation in c19 Books: An Exhibition (Charlottesville, VA: Rare Book School, 2012).

- 2 See Susan Otis Thompson, American Book Design and William Morris (NY: R. R. Bowker, 1977).

- 3 Quotations in this paragraph are from Theodore L. De Vinne, “Masculine Printing” The American Bookmaker 15 (Nov. 1892): 140-44.

- 4 For discussion of this aspect of De Vinne’s piece, see Megan L. Benton, “Typography and Gender: Remasculating the Modern Book,” in Illuminating Letters: Typography and Literary Interpretation, ed. Paul C. Gutjahr & Megan L. Benton (Amherst: U of Massachusetts PR, 2001), pp. 71–93.

- 5 See Irene Tichenor, No Art without Craft: The Life of Theodore Low De Vinne (Boston: Godine, 2005).

- 6 The best overview remains Ralph Thompson, American Literary Annuals & Gift Books, 1825–1865 (New York: H.W. Wilson, 1936).

- 7 Stephen Nissenbaum, The Battle for Christmas (New York: Knopf, 1996), p. 143.

- 8 Lea & Febiger, The Cost Book of Carey & Lea, 1825–1838, ed. D. Kaser, Philadelphia: (U of Pennsylvania PR, 1963), pp. 275-84.

- 9 David Kaser, Messrs. Carey and Lea of Philadelphia: A Study in the History of the Booktrade (Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania PR, 1957). For a discussion of H. C. Carey’s innovative use of stereotype plates, see James N. Green, “The Rise of Book Publishing,” in An Extensive Republic: Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation, 1790–1840, ed. Robert A. Gross & Mary Kelley, A History of the Book in America, v2. (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina PR, 2010), pp. 112-14.

- 10 Eugene Exman, The Brothers Harper: A Unique Publishing Partnership (New York: Harper & Row, 1965).

- 11 As quoted in the Knickerbocker 28 (July 1846): 73.

- 12 Gerard R. Wolfe, The House of Appleton (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow PR, 1981).

- 13 Ezra Greenspan, George Palmer Putnam: Representative American Publisher (University Park: Pennsylvania State U PR, 2000).

- 14 Ellen B. Ballou, The Building of the House: Houghton Mifflin’s Formative Years (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), pp. 37, 57, 68-69.

- 15 American Literary Gazette and Publishers’ Circular (1 Sept. 1864): 269.

- 16 See also American Literary Gazette and Publishers’ Circular (15 Dec. 1864): 109-10.

- 17 See announcement, dated 15 April 1879, from John Wilson & Son in PW (31 May 1879): 612 and The Cost Books of Ticknor and Fields and Its Predecessors: 1832-1858, ed. Warren S. Tryon & William Charvat (New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1949), p. 473.

- 18 For a discussion of the book trade during the Civil War, see my “The American Book Trade and the Civil War,” in A History of American Civil War Literature, ed. Coleman Hutchison (New York: Cambridge UP, 2016), pp. 17-32.

- 19 American Literary Gazette and Publishers’ Circular (15 Dec. 1863): 150.

- 20 American Literary Gazette and Publishers’ Circular (15 Jan. 1864): 209–10.

- 21 The earliest notice in Publishers’ Weekly was in the list of “Forthcoming Books of the Fall” of September 1872, but the work only appears in the “Alphabetical List of Books Just Published” in November 1873, see PW (19 Sept. 1972): 10 & (22 Nov. 1873): 566. The copyright notice in the published volume is dated 1873, the title page 1874.

- 22 “The Chemical Engraving Company of Boston,” Publishers’ Weekly (1 Aug. 1872): 115; Ballou, Building of the House, pp. 167-69.

- 23 Publishers’ Weekly (22 Sept. 1975): 652.

- 24 See Joel Munsell, Bibliotheca Munselliana: A Catalogue of the Books and Pamphlets Issued from the Press of Joel Munsell from 1828 to 1870 (Albany: Privately Printed, 1872).