Turnaround Time in a 17th-century Printing House?

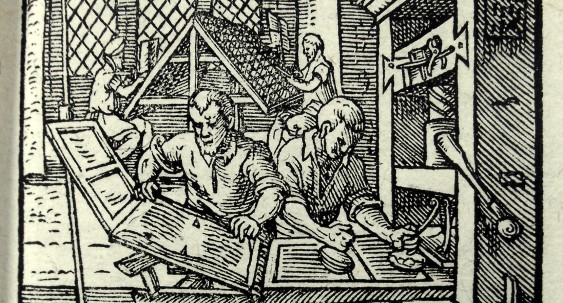

Detail from Jost Amman’s woodcut “Buchdrucker” (The Printer) from Das Ständebuch (The Book of Trades), 1568. Wikimedia.

Occasionally, I field questions from site visitors about various aspects of printing history. I generally reply by email sharing what I can on the subject and then direct them to other sources. Here’s a query that our readership should be able to answer.

… how much time it would take to set a book in type and print it in seventeenth century Europe?